Monday, August 29, 2005

1975: The Legend

There's a Simpsons Comic Book Guy love-at-first-sight story associated with this comic, involving a four-year-kid, a barber shop and a small town, all lit by the hazy glow of nostalgia. I'll spare you the pain of that, but I do want to talk about the book itself, Kamandi the Last Boy on Earth #29.

There's a Simpsons Comic Book Guy love-at-first-sight story associated with this comic, involving a four-year-kid, a barber shop and a small town, all lit by the hazy glow of nostalgia. I'll spare you the pain of that, but I do want to talk about the book itself, Kamandi the Last Boy on Earth #29.There are better comics. More skillfully drawn, more elegantly written, featuring more profound, subtle statements about the human condition. However, none of them feature a tribe of gorillas fighting across a post-apocalyptic landscape for the right to wear Superman's costume. Ah, Jack Kirby.

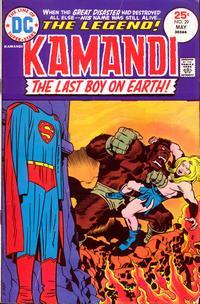

Just look at the cover. The bright red logo leaps out from the deep purple masthead that takes up the top third of the book, as comic covers were designed back then for maximum visibility on spinner racks and newsstand shelves. Patented Kirby Copy that I couldn't quite read at age four screams "When the Great Disaster had destroyed all else--his name was still alive--The Legend!" Below, in the background, you have Kamandi wrestling a mad, underwear-sporting gorilla in what looks like the heart of a volcano. But what draws your eye is what's in the foreground; the prototypical superhero's costume hanging from a cave wall--wrinkled, slightly off-model for the DC house style, and mysteriously empty.

Now, Kamandi was a picaresque. Each issue, in his aimless quest to survive, he would stumble across a new species of intelligent animal--lion game wardens, tiger armies, on and on. In this particular issue, he encounters a cult of apes who have passed down Superman's clothing as a kind of four-color Shroud of Turin. They worship Superman's story, but through the mists and half-truths of oral history, the details and even the basic point have become very fuzzy. They worship Superman's feats, but not their meaning. Accordingly, the gorillas have organized their society into ritualized reenactments of Superman's powers; pushing giant stones, taking mighty leaps, etc. Contrivance forces Kamandi to compete against an aggressive gorilla for his life and the right to the costume. He survives thanks to his wits and the help of his astronaut friend, the humanoid "mutant" Ben Boxer.

Much of the comic is the standard Kamandi formula, the power of which was recently decoded by Tom Spurgeon. But there's something about that empty suit that, for me anyway, gets straight to the heart of superheroes, their appeal, and how they've gone off the rails in the last couple of decades. There's the joy of absurd ideas, leavened with a sadness represented by the hollowness of that image--a Superman costume with no one inside. He's gone, likely dead fighting against whatever "Great Disaster" turned the world upside down. Yet there's his suit, his memory kept alive in a completely different context. The story is there, but it has been misinterpreted by an audience it was never meant for.

These days, DC Comics pitches its old kids concepts towards 35-year-olds by injecting a psychological pseudo-realism and grisly violence into characters not designed to bear those burdens. As fans lap up fin-headed super rape in satellites 23,000 miles above sea level, that costume and those misguided apes seem somehow prescient. Any given issue of Superman of Batman today is a 22-page empty suit, showing the same ritualized reenactments divorced from a context in which they make emotional or literal sense. And a readership of aging apes deludes themselves into thinking that increasingly terse violence approaching nilhism is sophistication. I recently read a high-profile DC comic which consisted entirely of one group of supervillains brutally torturing another group of supervillains, page after page. It was well-written and drawn for what it was, and may even be a commentary, if a shallow one, on the Gitmo-izing of our society. But still, it's a 22-page torture story packaged as cheap thrills for mainstream audiences. It makes me uneasy to see such deliberate, delineated cruelty become our casual entertainment. Call it the hazy glow of nostalgia, and I suppose it is, but I don't get that feeling from Kirby's Kamandi.